Libby’s sister, Kim, responds to the breast cancer screening guideline update

Say the name Libby and many of us in the breast cancer community immediately feel an ache in our hearts.

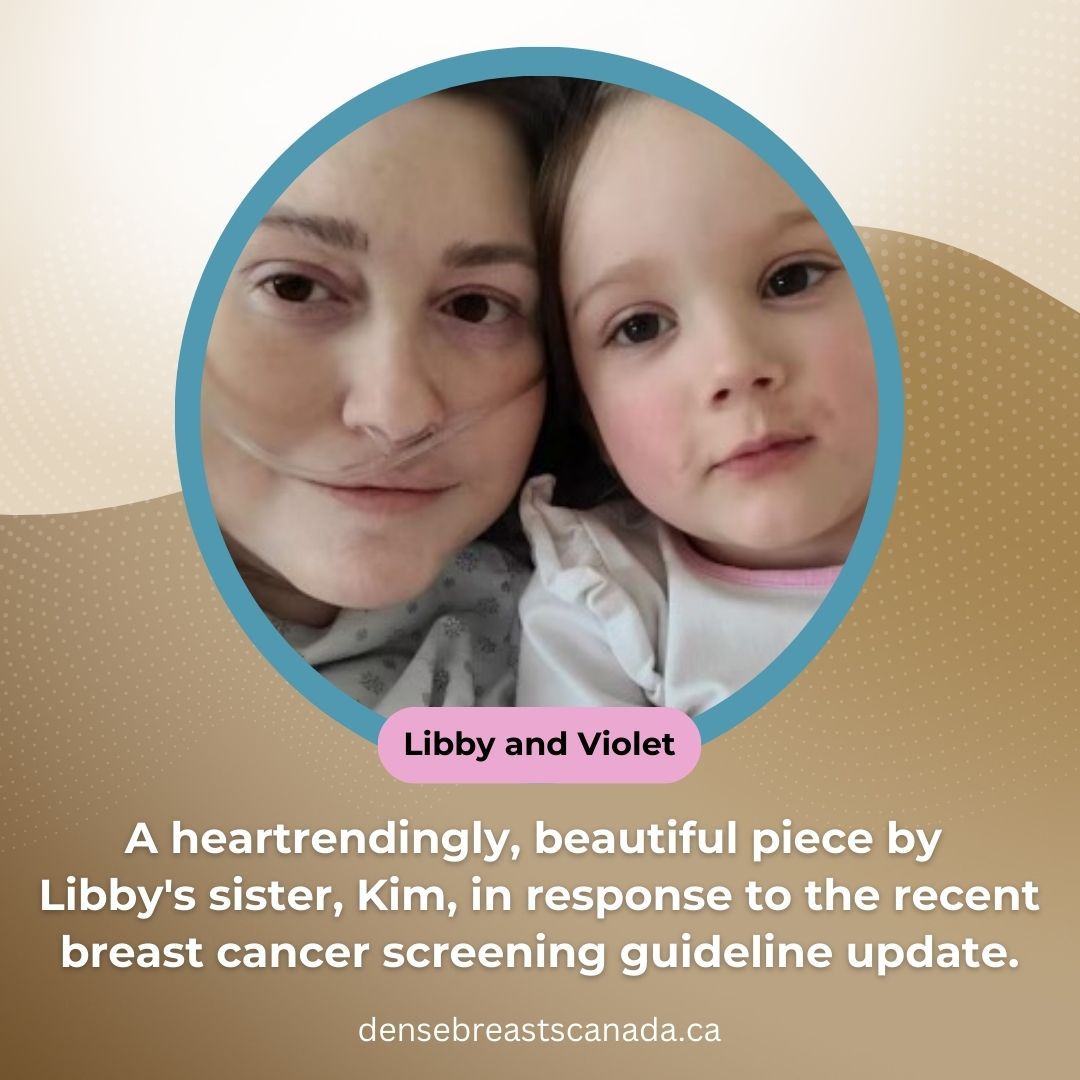

Libby’s sister, Kim, has written this heartrendingly beautiful piece in response to the recent breast cancer screening guideline update. It has been shared with MPs on the Health Committee and Status of Women Committee; the committees are writing a report on the breast screening guidelines right now. With much gratitude to Kim, we share her words with you and hope you will continue sharing.

My mother was 48 years old when she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. Under the 2024 draft screening recommendations from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, she would have been too young to have received a screening mammogram but have no doubt that if it weren’t for a screening mammogram my mother would have died or, at the very least, I would have lost her piece by piece to this painful and disfiguring disease.

Despite watching my mother endure cancer treatments in my early teens, my own risk for developing breast cancer never crossed my mind. It never crossed my sister’s mind either. My sister, Elizabeth Joan Wilson (better known as Libby), was pregnant with her first child when she brought a lump in her breast to the attention of her obstetrician. She was reassured when she was told that this was likely just a blocked milk duct. In 2019, Libby was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer only short months after giving birth to her daughter, Violet. Less than five years later she would be dead.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care breaks down the risks of not screening women into small, palatable pieces. They tell us that if 1000 women aged 40-49 were screened only one life would be potentially saved in a ten-year period. Another 18 to 19 women would have breast cancer but they would still be alive. Of course, most of us realize that statistics rarely tell the whole story. When a patient is diagnosed with breast cancer, it isn’t a watch and wait situation. Leaving breast cancer undiagnosed and untreated in younger women will leave these women vulnerable to more aggressive treatments and deadlier outcomes. There is no justification for allowing women to go untreated for up to a decade for want of a mammogram. What may appear to the Task Force to be simply statistics are mothers, daughters, sisters, and friends. They are not expendable.

After learning of my sister’s cancer diagnosis, I asked my family doctor about increased screening and was told that “we don’t want to look for something we don’t want to find”. It was only after a referral to the Breast Health Clinic that I discovered that I am considered a high-risk patient. Starting at 32 years old, I began a comprehensive screening program as advised by experts. I learned that my risk of breast cancer was increased by not only my family history but also by my breast density. For me, gaining the information I needed to protect my own health required a crash course in the deadly nature of breast cancer. Receiving breast cancer screening and information shouldn’t be more complicated than solving a rubrics cube. It shouldn’t require waiting till your family member is dead or severely ill to receive screening. Family physicians should have the information and screening guidelines they need readily available. Instead, the Task Force is advising family doctors that breast screening may cause women too much anxiety. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if my sister had been immediately sent for imaging when she first showed her breast lump to her obstetrician. Would the time saved in receiving treatment have had the potential to save my sister’s life?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force have changed their breast cancer screening guidelines to begin at 40. They note that this decision was made because the incidence of breast cancer among women ages 40-49 has increased since the year 2000. It is disturbing to me that the Canadian Task Force has disregarded this information.

Dying of cancer isn’t simply going quietly into the night. For many people it involves years of suffering. My sister can’t tell you her story because she lost her life to breast cancer. Instead, I will tell you what it was like for me to watch my sister die.

Before her treatments even began, Libby was crippled by her diagnosis. She spent many days doing nothing but crying, sleeping, and researching survival rates but, as Paul Kalanithi wrote in his book When Breath Becomes Air “[g]etting too deeply into statistics is like trying to quench a thirst with salty water”. The more Libby read about the aggressive and lethal nature of breast cancer in younger women the more frantic she became, falling into a deep depression that often left her unable to cope at all.

On my days off from work my sister would ask me to watch her baby because she had been up all night, sleepless from the worry of future surgery, chemotherapy, and her own mortality. My niece and I would spend many happy hours going to the park across the street from my house. I would push her in the baby swing, and she would laugh and kick her feet. I couldn’t help but feel though, that it should be my sister witnessing the joy of this tiny little person and not me.

The first stage of my sister’s treatment was chemotherapy. Her friend, who was a hairstylist, came to my sister’s house and cut her long dark hair off. My sister tried to make the event fun and light, even inviting a few close friends over and trying quirky styles like a bob and a Mohawk before becoming completely bald. For the first time, my sister looked like a cancer patient, bald and weary from late nights of worry. She asked to take a group picture of us all and I tried to wipe away my tears before the camera captured them.

After chemotherapy, my sister had a mastectomy. She would ask me to come over and help her to empty the Jackson Pratt drain that hung from a tube inserted into her incision site. I would squeeze the bulb of the drain, emptying her dark red blood into a measuring cup so we could keep track of the drainage. When the drain came out and the bandages came off, my sister struggled with the disfiguring results of the surgery. A large scar across her chest and a single breast that she jokingly referred to as her “uniboob”, along with her bald head, and an arm swollen from lymph node removal were enough to make my sister feel too self-conscious to leave the house.

The final stage of my sister’s treatment was radiation. When Libby couldn’t find childcare for her daughter, she would have to take her with her to the hospital, pushing her wide-eyed little girl through the dark dungeons of the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in her stroller. She once told me that since she couldn’t bring her baby into the radiation room with her, she would sometimes be forced to look around the waiting room for a kind face and ask a total stranger to watch her baby while she lay on the hard table of the radiation machine.

We all breathed a sigh of relief when my sister’s treatments ended. She started growing back a little bit of hair. Enough for a pixie cut. She went back to work and back to parenting. For a moment it seemed that my sister could have her life back and if that was the case, maybe all of that suffering would be worth it.

All that hope was demolished when it was discovered that Libby had a single bone metastasis to her sacrum. Despite aggressive treatments, Libby’s cancer had spread and was now stage 4. While the world watched the news of the COVID-19 virus play repetitiously on the news, Libby lay frozen in bed now aware that her death had already been written.

It felt to Libby that no one cared about her life. Her terminal cancer was simply accepted as an unfortunate death sentence, and she felt that no one was listening. Libby did not want to lay down and die so she screamed her pain out into the echo chamber of the internet hoping that someone would hear her. She wrote late night poetry and documented her daily struggles on Twitter and TikTok. She presented dying from cancer as she saw it, merciless, painful, and hopeless.

Following her diagnosis with stage 4 breast cancer, Libby made her way through many lines of treatment. The first one made her vomit relentlessly. The next one made her hands and feet blister to the point that it was painful to walk. Her final treatment option was IV chemotherapy, and this came with every side effect imaginable. Nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and relentless headaches all for the hope of living for just a few more weeks. While many people may romanticize the notion of ‘living like you are dying’ I must only assume that these people have no idea what ‘dying’ really is. Dying isn’t a finite moment when your breath suddenly stops. Libby told me that living with cancer was like dying a million tiny deaths and grieving for each thing that cancer cruelly took away. She grieved for the loss of her hair, her fertility, her mobility, her hopes, her future, and eventually her present.

Libby considered MAID when her symptoms started getting worse but when her daughter asked her if she was going to die, she responded that she would do her best to live for as long as possible. When Libby’s breathing became difficult, she discovered that her lungs were filling up with fluid. She had a drain placed in each lung so that her home care nurse could drain her lungs every other day. At this point, my sister was no longer able to even take the long baths that she had loved all her life.

When Libby was no longer able to walk to the bathroom, my brother-in-law bought her a commode chair. My niece had just started potty training and eyed my sister’s new adult sized potty suspiciously.

I lost count of how many times Libby was admitted to the hospital, each time bleaker than the last. By 2023, my sister’s cancer had spread to her lungs, brain, and bones. In March of that year, she had to have one of her femurs replaced but despite this she would spend the rest of her life almost completely bedbound.

Libby would give me shopping lists and I would go to Walmart to buy her the items she needed. I felt self-conscious the first time I placed her adult diapers in my shopping cart remembering a time, not so long ago, when Libby and I may have chuckled at the sight of a woman as young as myself gazing intently at the different types of adult diapers.

Libby’s life came to halt on the night of August 21’st, 2023. Her femur had fractured from the simple action of turning in bed. She was carried down her stairs and into an ambulance by EMS that night, she would never see her home or her beloved pets again. On August 31’st at 3:15pm Libby took her last breath. I cleaned the dried blood from her nose and brushed her short hair, thin and soft from her last round of chemo, into a little combover. She would have hated that little combover. I tentatively placed my hand on her cold arm, taking one last look at my sister. I felt weightless and disoriented as I left the hospital for the last time.

Now when I visit her, I stand at her grave.

Maybe Libby’s life couldn’t have been saved but other lives can be. The Task Force may believe that anxiety is too much for women to bear and is an unreasonable harm. Sure, maybe they’ll let you have a mammogram if you ask your doctor, but this isn’t good enough. The U.S. recognizes that breast cancer rates in younger women have increased in the last 20 years. Canada needs to recognize this too.

Kim Porter